DAAS, KKH - Artistic Research | 2020-2022

Permeance:

Unearthing the Remnants of the Zinc Industry

The ‘Permeance Project’ is a research initiated during Decolonizing Architecture Advanced Studies at the Kungliga Konsthögskolan led by professor Alessandro Petti and Marie-Louise Richards. Starting from the personal urge of connecting to my family heritage and landscape I have followed the traces of the cadmium contamination in the river Dommel upstream and into the past, uncovering a chain of events which talk about colonialism and extractions. From the zinc smelting industries across the Belgium border to the Emu Foot Province in northern Queensland, permeability reveals,

through the contaminations of river biota and the riverbed soil, how Australian colonial history has become linked to the pollution of the river Dommel.

Exhibited at Casa Punto Croce, Venice, May 2021

To read the full research project, download the 'Permeance' booklet HERE, or read HERE >>

In depth read: Essay on Permeance HERE.

Essay on Polluted Art HERE

To support the ongoing research >>

.gif)

Mapping Key,

Circular Chromatographies

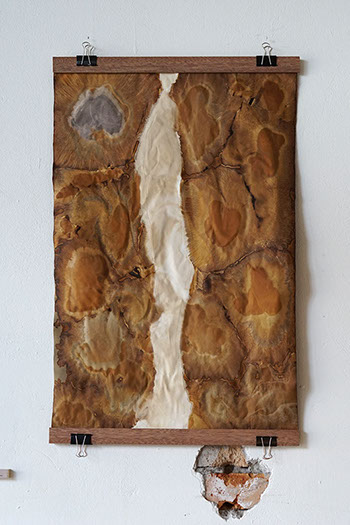

Mapping I,

Collaborative Chromatography

62 x 100cm

Mapping II,

Collaborative Chromatography

62 x 100cm

Mapping III,

Collaborative Chromatography

62 x 100cm

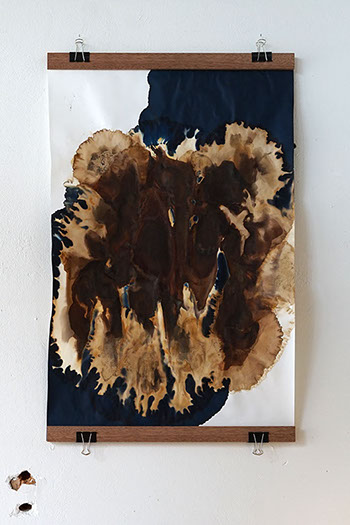

Mapping IV,

Collaborative Chromatography and Cyanotype

62 x 100cm

^top

Mapping V,

Collaborative Chromatography

Mapping VI,

Collaborative Chromatography

The river

The river Dommel is a natural fluvial system extending for the length of 146km, originating in Peer, Belgium and joining the river Meuse in the Netherlands. Following my initial curiosity at the sight of the scraped down river banks of the Dommel, I began noticing multiple anthropogenic interventions in the river along

its course; these were consequential measures in response to the high levels of cadmium and zinc contamination in the soil of the river bed. The pollutants were emitted by the nearby zinc-ore smelters in the Flemish Neerpelt, right across the Dutch border, which have been active in producing zinc blocks and sheets for over 125 years. The process of zinc extraction and fusion from metal ores was particularly polluting in the past due to the release of toxic gasses and contaminated water with dissolved zinc and cadmium particles. These industrial waste waters have been dumped for over a century into a ditch, the Eindergatloop, which runs along the border of the terrain, where the water stream carried the pollution further along to merge into the river Dommel. In the 1980s, after 85 years of uncontrolled industrial discharge, it became evident that the river bed of the

Dommel had particularly high levels of zinc and cadmium, both heavy metals which settle and attach to the sediment once the water stream slows down. Soil decontamination projects Dommel, the Netherlands the river have been carried out by the organization Waterschap de Dommel, by scraping the river bottom and banks, and displacing the contaminated ground elsewhere. Despite the reduction of direct pollution from the smelters, the concentration of zinc and cadmium in the river sediment is still dangerously high for both aquatic and terrestrial creatures. These metals have permeated through bodies, from the river into the aquatic flora, and from the displaced earth into the nearby vegetation. Cadmium has also permeated into the bodies of macro invertebrates such as earthworms, and microalgae such as diatoms. These biotas serve scientists as river pollution indicators, and in this story, cadmium and zinc will act as tracers as they continue their permeating journey, leaving behind a trail which reveals how entangled, contaminated and polluted our beyond-human encounters really are. The leitmotif of this story is the ability of zinc and cadmium to permeate through time and environments, and as we will discover, it also has left a thread to follow to its geological origins in Queensland, Australia.

Emu Foot Province.

Queensland, Australia

The zinc industry in Neerpelt operated under various company names, over time fusing with other corporations such as Umicore, the Australian Zinifex and nowadays, Nyrstar. In 2000, Zinifex began importing raw material from the Australian Century Mine, also owned by the then Zinifex corporation.

Between 1999 and 2016, Century Mine was one of the world’s largest open pit zinc mines. Located in North Queensland, an Australian region known for its vast mineral deposits of zinc, copper and silver, the mine sits 250 km north-west of the city of Mount Isa. The surrounding territories to Mount Isa have been the land of the Kalkadoon people for over 60000 years, an indigenous tribe that resided in the Emu Foot Province. Their land was dispossessed in 1884, after the Kalkadoons’ final battle against colonization by white settlers. This war is remembered today as ‘Battle Mountain’, during which 150 Kalkadoon natives were massacred for resisting settlers. Over the course of the following 6 years, between 1878 and 1884, it is estimated that up to 900 Kalkadoon people lost their lives while defending their people and land from incursions. 255 years prior, in 1606, Dutch colonial navigator Willem Jansz had arrived as the first European in Australia by approaching the shores of northern Queensland. His explorations and first European mappings of the continent opened the doors for Australia’s European colonization and exploitation.

Through the lens of permeability, the chain of events uncovered by soil contaminations and abnormal biota indexes have led upstream to Australian colonial history, and as a result, the story of the Kalkadoon people has become linked to the pollution of the river Dommel.

to permeate,

permeability,

permeance,

permeation,

permeating:

the action to diffuse through or penetrate something

In this research I propose permeability as a conceptual lens through which to approach the entanglements of earthly life. In many ways, permeation is similar to the organic process imagined by Donna Haraway as a ‘zoophagous chain of critters engulfing one another’. However, I envision permeability also as a mode of operating through principles of physics and chemical processes, as well as molecular exchanges and biological

absorptions. In the book ‘Staying with the Trouble’, Haraway also reflects on rehabilitation, or making livable again, if we manage to recognize “the porous tissues and open edges of damaged but still ongoing living worlds” [1]. Comparably, permeability can also stimulate exchanges between bodies and natural entities.

Through a permeable vision we all, living and non-living, become part of a greater, more penetrable world. The impermeable membranes, so desirably sought after by modernity’s categorizations, deteriorate into a pile of compost which stimulates exchanges of substances, nutrients, molecules and microorganisms.

Permeance also implies an awareness of our participation in symbiotic relationships with Earth. Dismantling our parasitic use of the environment and its forms of life requires us to permeate through them in mutualistic, reciprocal encounters. Anna Tsing in ‘The Mushroom at the End of the World’ writes that “we are contaminated by our encounters’’ [2]; we cause and absorb pollutions through our interactions with earthly beings and matter. We all, living creatures, also carry the record of past encounters. This is the key to evolution; it is in the matter that composes our beings that we hold the histories of our contaminations. Not only do we carry pollutants in our biology, in our permeating encounters we contaminate through social interactions and relations to the land—colonialism and extractions are among those practices—generating a “contaminated diversity [which] implicates survivors in histories of greed, violence and environmental destruction” [2]. Permeance uncovers the tracks of such happenings, allowing us to look into the past by following contaminations along a chain of events. Tsing states that in order to acquire the necessary skills to be able to live in ruins, we must be able to recognize and accept these contaminations. In contrast, the notion of permeability enables us to trace and understand the ruins we inhabit. This emphasis on permeance as past remains can be aligned to the exposition of contamination as ‘tracer’, as Tsing writes in ‘Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet’: “Our modes of noticing, however, are themselves monstrous in their connection to Man’s conquest. Much of what we know about ecological connection comes from tracking the movements of radiation and other pollutants.

Contamination often acts as a ‘tracer’—a way to see relations. We notice connections in part through their ruination.” [3]. This research indeed follows a history of pollution, which has been the ruination of both ecosystems and indigenous cultures. Unfortunately, these histories still need to be uncovered, as the ability to notice has yet to be refined by the Western eye. Too often we—in the West—are blinded by our perception that our actions are impermeable. Instead, permeating is only possible if we see beyond our limits and borders: rivers flow between confines; histories of pollution can be displaced but not

erased; contaminations can be absorbed but do not vanish; material histories can take you back to their geologies; and along them stories of extractions and colonial violence emerge. Permeating unsilences.

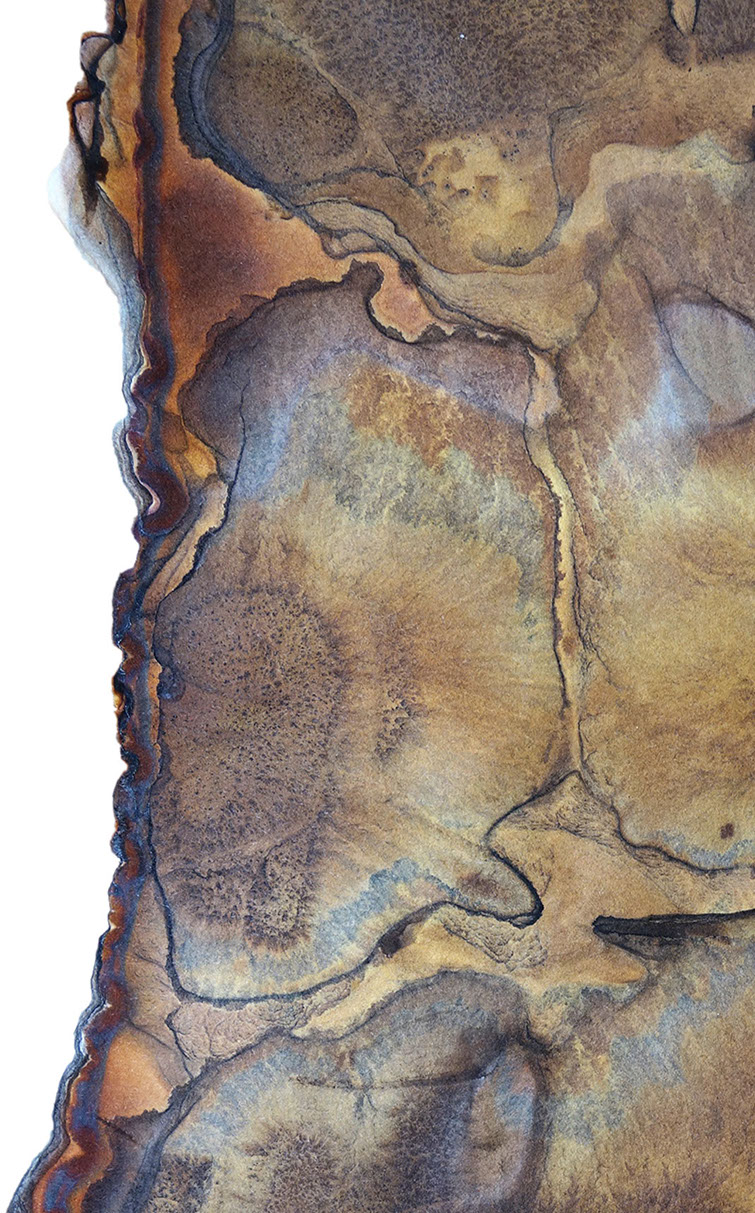

Permeance

Mapping

Situated between a scientific backdrop and artistic production, this research materializes through the medium of soil chromatographies, utilized as a form of sustainable, cameraless slow photography, which gives agency to contaminated earths by revealing their chemical compositions. Through sampling along crucial points of the river, the soils used to create the chromatography actually unearth a mapping of pollutants. The result is a fundamental critique to both photography and cartography as anthropocentric and modern readings of the world. Moreover, through an alternate mapping, I wish to highlight the innate problematic of cartography as tools for colonization of land and people. In opposition, the proposed mapping of the river Dommel blurs the lines -through contaminationsbetween art and science, dismantling the

modern from a western positionality and proposing a demodern alternative. By critically reviewing the dominating human centred practice of mapping, I searched for a new balance between my presence and the agency to the voices of living and non-living bodies.

Through collaborative chromatographies, I conduct -bring together- the voices of riverbed soil samples, permeating into each other, to speak about contaminations and map the voice of the river.

[1] Harawaw, D.J. (2016). Staying with the Trouble. Making Kin in the Chthulucene. London, England: Duke University Press

[2] Tsing, A. (2015). The Mushroom at the End of the World, On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton, USA: Princeton University Press

[3] Tsing, A., Swanson, H., Gan, E., & Bubandt, N. (2017). Arts of living on a damaged planet. Minnesota, USA: University of Minnesota Press

Contaminating [short fiction]

My history lies among the geologic layers of my forefathers and mothers. For millennia I have rested in peace, left untouched, my land respected and cared for. Strangers saw value in me, they cut into the Earth, left an open sore where I used to lay. They wanted me, extracted what they were looking for, ripped me open, melted away my body, washed away what they feared, discarded me as waste.

I entered the river, my body rested heavily on its bed. This became my new home. Parts of me were restless, I looked for other places to lay. I entered the body of earthworms. I searched among diatoms, but most of them died. I approached the water plants, then the plants on the river side. I lingered there for a while, then grazers came along and I lay in their bodies, I rested in their livers.

And now that you have come to break my peace, I realize that my journey to my resting place continues.

I enter through the skin of your fingertips.

I am cadmium.

© Steffie de Gaetano 2021